FROM REVERENCE TO RAPE, The Treatment of Women in the Movies, Third Edition (2016)

Molly Haskell, with a new Introduction.

New Foreword by Manohla Dargis

A revolutionary classic of feminist cinema criticism, Molly Haskell’s From Reverence to Rape remains as insightful, searing, and relevant as it was the day it was first published. Ranging across time and genres from the golden age of Hollywood to films of the late twentieth century, Haskell analyzes images of women in movies, the relationship between these images and the status of women in society, the stars who fit these images or defied them, and the attitudes of their directors. This new edition features both a new foreword by New York Times film critic Manohla Dargis and a new introduction from the author that discusses the book’s reception and the evolution of her views. (Book Cover)

Introduction

In 1991, while preparing to teach my first course at Columbia, I found in a quarterly on feminist film theory a discussion of my 1973 book, From Reverence to Rape: The Treatment of Women in the Movies. It was treated as a sort of prehistoric text, once important but—now that theory had come to save the day—obsolete. The writer noted that for all my strengths and weaknesses, everyone had missed my one fatal defect: I was “an uncritical celebrator of heterosexual romance.” After the first moments of irritation and amusement passed, I thought, yes, I plead guilty to the charge. This was, after all, the early seventies when the term heterosexual had not become problematic, one item—and presumably the least hip one—on the lifestyle menu or the academic agenda.

The unarguable contention was that the stars, always in the configuration of the heterosexual couple, didn’t include most of us—the short, the swarthy, the rotund, the ethnic, the homosexual, the nerdy, the awkward—those of us who didn’t have a date on Saturday night, which was all of us some of the time and some of us most of the time. They were a patrician ideal, impossibly smooth and glamorous, the creation, ironically, of a group of short, swarthy, cigar-smoking Jewish moguls who were only one generation away from the shtetl and who projected their assimilationist yearnings onto the stars whose careers they owned and tended.

In an impulse that went against the grain of feminist thinking at the time, I wanted to show how women had in fact been better served by the notoriously tyrannical studio system than they were in the newer, freer, hipper Hollywood of the (then) present. This has since become a truism, but in 1974 it was heresy. However unreflective of the actual social power of women, the female stars of the thirties and forties radiated an enormous sense of authority and had the salaries to back it up. The spirited and challenging woman, if not a universal reality, was a powerful and ever-present idea. (And there were enough female headliners in politics, sports, the arts to give resonance to the authority and swagger of stars like Dietrich and Garbo, Davis, Crawford, Hepburn, Dunne, Rosalind Russell, Colbert.)

If fictional heroines wound up following the traditional line on what women should do—settle down and become compliant wives—they nevertheless offered enough subversive resistance along the way to indicate that all was not peaceful and placid in the supposedly natural order of things. As a metaphor for the way movies would serve up the obligatory happy ending, but with an acrid aftertaste, I pointed to The Moon’s Our Home, a 1936 comedy in which Margaret Sullavan, playing an actress who has agreed to give up her career for her Park Avenue husband (Henry Fonda), suddenly bolts, goes to “Idlewild” (now Kennedy), and is boarding a plane to Hollywood when Fonda comes with some paramedics to capture her. The last shot of the film has Sullavan in a straitjacket, in the back seat of the ambulance, looking up at Fonda with the smile of the blissfully subdued.

Not coincidentally, two of the movie’s screenwriters were husband and wife team Dorothy Parker and Alan Campbell, possibly the most undomestic couple ever to be joined in marriage and housekeeping. My original point was that as with many such films, what we remember is not the scene of surrender but the previous ninety minutes in which the heroine more than holds her own in the battle of the sexes. As in Shakespeare’s plays, the happy ending is a convention that satisfies a need for order and resolution while leaving ample room for doubt as to the completeness of the promised joy.

For most feminists, there is and has always been a split between the forward-looking conscious self, politically progressive and “emancipated,” and the dark recesses of our fantasies, in thrall to the past and to the movies that provide a pathway back. With a bow of acknowledgment to Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, who used the phrase somewhat differently as the title of one of their collections, I had begun to think of myself as stranded in no-man’s-land, like a soldier caught in that exposed area between Allied and German trenches in the First World War. Or a tennis player, caught in the one position on the court where you have no purchase on the ball—too far from the net to volley, too close to try for a ground stroke.

To me, my engaging with film on a feminist basis left me in a friendless place. For the film buffs, film critics, and journalists with whom I had the most in common, film was a first priority and the issue of women entered into it secondarily. Film was my first allegiance as well, but I couldn’t help responding in an unusually intense way to the man-woman relationship and its meaning for both sexes. It seemed to me so much what film was all about, so much what had drawn me to film in the first place, and, in some as yet undeciphered way, so much the secret of my choice of metier, that I was incapable of pulling away to a more detached, less emotional position; no more could I use film—as so many intellectuals do—as slumming escapist fun while I used my mind for more “serious” things.

I felt a strong rooting interest in women, in what enabled them to rise above the limitations imposed on them, in how they found succor, in their camaraderie, in the radical urges that lay germinating, concealed beneath correct behavior or erupting into wild remarks, comic confrontation, swagger, seduction, and battles of independence. “Women are compromised the day they’re born,” says a rueful Paulette Goddard in The Women. I wanted to know how they handled the compromise, wrested some triumph from the deal. And how each case, each movie, each director differed; even within the career of a director known as misogynist, different actresses changed the coloring and therefore political meaning of a character and film.

The word misogynist, once flung out as a judgment from on high by yours truly and others, has come to seem woefully inadequate, a sort of one-size-fits-all epithet and conversation stopper that is much too narrow for the variety of attitudes and feelings that color any particular vision of woman. Female characters find their way onto page or screen through a wide prism of authorial appetites and aversions, an emotional spectrum that includes lust, possessiveness, fear, indifference, contempt, worship, idealization, depersonalization, repugnance. More important, rarely are any of these—say desire, dislike, and fear—seen in discrete simplicity but, rather, more often play out in complex ways and in different combinations. They are not even separable from “love of women,” at the positive end of the spectrum, a term that itself tells an incomplete story. Where love is, there may or may not be lust or attraction, there may or may not be a fear of dependency, and (most important and rarest of all) there may or may not be sheer liking and curiosity.

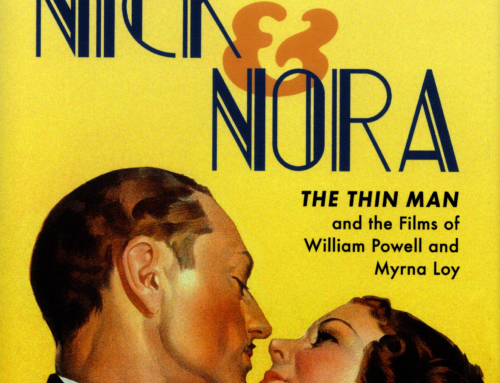

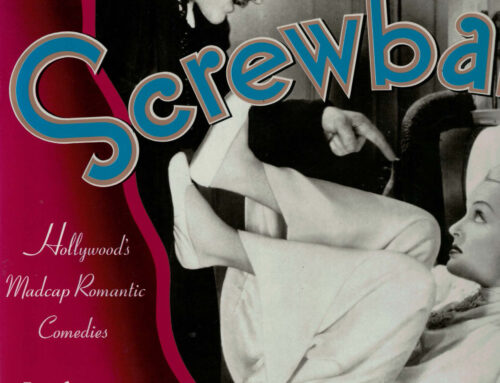

The word misogyny belonged to a different era, one that presupposed a straight male-on-female orientation and set of attitudes. The romance between Man and Woman, with its two possible endings, happy (marriage) and unhappy (separation), was the foundational ideal of the traditional love fantasy enshrined in movies—one to which I was, I confess, deeply attached, perhaps even myopically so. I can still love the screwball comedies, women’s films, and film noir of the thirties and forties (which crucially includes their often subversive sexual dynamics) but also welcome the bristling and sometimes bafflingly egalitarian world for which they only partially prepared us. The ground has shifted tectonically: even “endings” are provisional, and heterosexual love, once the default setting, has had to cede its sovereignty to other forms of attraction and relationships: gay, bisexual, transgender. Like identity itself, love, misogyny, and their myriad offshoots and variants are not gender bound.

What I was culpable of, it seems to me—along with most people who were discussing culture from a feminist viewpoint—was subscribing to an oversimplified dichotomy between male and female, oppressor and victim, which implied a utopian agenda. Equality could be won because the enemy—the “patriarchal oppressor”—was without. The theory of the gaze in cinematic spectacle, that is, the visual objectification of woman in the eye of the male beholder, always seemed too monolithic, a narrow one-way street, allowing no room for the pleasure women take in looking and being seen. But if we hadn’t believed in and given voice to certain rhetorical simplifications—using the pronoun “we,” for example, to embrace blithely and without fear of contradiction the hopes and grievances of one-half of the human race—we never would have spoken out in the first place.

It seems obvious, now, that if gender parity has not been realized overnight, it is because the impulses that give rise to inequality lie deep within, ancient and universal. Patriarchy is a symptom, not a root cause, of the need to deny and repress the matriarchy into which every child is born, the maternal womb from which we issue, the maternal presence that overwhelms our early life.

Our image-saturated culture everywhere presents examples of our ambivalence toward powerful women and our lingering inability to see older, authoritative women as desirable in the way that older men of consequence surely are. The double standard of aging that allowed Cary Grant and Fred Astaire to play Romeo to increasingly younger Juliets, decade after decade, has not changed much when we accept De Niro and Pacino, Redford and Eastwood, playing lovers of much younger women, while reviewers absurdly reproached Emma Thompson for being too old to play the older sister in Sense and Sensibility!

The parameters have shifted and the lens has widened. The gaze is turned on men by women, on men by other men, on women by themselves. The expanding of opportunities for older women that I note in the last chapter continues. Meryl Streep and Helen Mirren are enjoying busy and glorious late careers, and one of the finest films of 2015, 45 Years, shows a fearless and sensually mysterious Charlotte Rampling, uncosmeticized at 65. But the backlash is fierce. Men still dominate the screen, get their revenge, or compensation, by rejecting women altogether. Male bonding to the rescue as doofus desencendants of Animal House regress in Judd Apatow bromance comedies; viable hunks and their second bananas flee to Las Vegas for horny hungover bonding sprees. And in various states of action and reflection, a new genre of geezer-pleaser films has sprung up to accommodate A-list stars on Medicare like Michael Caine and Harrison Ford, Bruce Willis and Sean Connery.

From our discomfort with the idea of mature women as models and magazine covers, our preference for young bodies in love scenes, can’t we infer that the older woman holds some residual terror for both sexes, and that if there is a “backlash,” some of its energy may be coming not just from patriarchal white males but from women themselves?

Having not yet found the conceptual path to understanding these various conundrums, I nevertheless tried to suggest in From Reverence to Rape some of the difficulties inherent in taking a strict feminist view of a form as complex, as full of contradictions, as hooked into the secret closets and shadowy recesses of the viewer’s psyche as movies. This wasn’t a popular idea with the theoreticians who saw film simply as another arena in which women were used, abused, or oppressed.

For seventies feminists, the career woman of the thirties and forties movies was a stock figure of ridicule. Invariably, she was a workaholic or a spinsterish professional (Ingrid Bergman as the bespectacled psychiatrist in Spellbound) who, finding the right man, shed her glasses and, like a female Clark Kent, blossomed into a figure of desire. The idea that a career had to be surrendered on the altar of matrimony or that there might be a conflict between the two was, to latter-day feminists, anathema, an example of Hollywood propaganda in favor of patriarchy and the propagation of the species. The possibility that this drama might also express a conflict within women themselves, or that there might be some downside in releasing women, and men, from their different and time-honored roles safeguarding the family, was not to be countenanced.

So persistent is the fear of the powerful woman—the demonized feminist, the she-monster who proliferates in decades of significant progress by women—that it must reflect a deep-seated taboo against combining the awesome biological power of motherhood with status outside the home. It violates some fairness doctrine, an innately held belief in the division of powers. The absence of mothers, as others have noted, in genres that celebrate sexual equality (the screwball comedy) or female ambition, is significant. It’s impossible to imagine Katharine Hepburn’s Dorothy Thompson–like journalist in Woman of the Year as having a mother. Hers died when she was young, and she has acquired, in her feminist aunt Ellen (Fay Bainter), an idol and surrogate parent. When Bainter accepts Hepburn’s widowed father in marriage, Hepburn—whose marriage to Spencer Tracy is a sham, a structure designed to allow her to remain essentially as she was—is crushed. “I always thought you were above marriage,” she tells Bainter in one of the movie’s most poignant moments. Being a mother or even a loving wife draws on different energies and emotions than being a newspaperwoman does (although, in a rose-colored bit of male chauvinism, Tracy is granted prowess in all three domains).

I was less interested in categorical signs of oppression and victimization than in diversities of sickness and health; less interested in how “Hollywood” defined women than in how Woody Allen or Ingmar Bergman defined them, or how different women survived the Pygmalion-like hold of these complex, women-obsessed artists. How Eva Dahlbeck might give weight and meaning to one aspect of womanhood, and Harriet Andersson to another, how some actresses profited from these mentors while others were, if not destroyed, used up by them and unable to forge careers apart from them.

To other critics, women characters might seem to be, if not an afterthought, just one of the many ingredients “produced” by the story, whereas to me they were its fulcrum. A writer came up with a story in order to wrestle with feelings about women, to present a certain view that would contain and assuage, enhance, adore, lust for, avenge, ridicule, destroy, surrender to the image of woman he carried within him. The inextricable link between the woman on the screen and the feminine side of the artist, and, no less important, the identification of females in the audience with males on the screen, made the whole process of film viewing considerably more complicated than a simple male-vs.-female equation could account for.

Try as I might to keep aesthetic considerations paramount, I could never separate John Huston from his view of woman as a creature who in look and entertainment value came second-best to a fine Irish thoroughbred. That woman are less fun than guys or horses—or the current boys’ toy, bombs—is of course a typical adolescent view. I should know: I once held it. Not just men but women, too, find refuge in all-male stories and fantasies of male rescue. The fact is, we are all, in some measure, more comfortable with maleness than with femaleness.

The wider moral latitude granted men in all areas of life begins at a deep emotional level but is evident in film after film, where the sleaziest of male characters (especially if played by a charismatic actor) is forgiven, even swooned over, while a wicked woman is beyond the pale, rendered witch-like, then blown away to cheering approval.

When, in a class on women in Film Noir, I showed The Maltese Falcon, the students forgave Humphrey Bogart everything and Mary Astor nothing. The fact that the lying Bridget O’Shaughnessy was a woman of scant resources, trying to stay afloat by guile and sex appeal, carried no weight with them; while Bogart, professing pious allegiance to his dead colleague, could have murdered twenty people and gotten away with it. Charm he had in spades, and he was a man. Male superiority is a stabilizing force, as we can see from the increased violence and instability in the relations between the sexes that has accompanied every step in the movement for equality. Do they really have more charm, more value? Or must we overvalue and romanticize them in order to create superior creatures worthy of the compromises we make for the sake of love, marriage, and family? The stories are legion of powerful intelligent women—Simone de Beauvoir, Hannah Arendt, Mary Wollstonecraft come to mind—who overlooked the flaws or exaggerated the attractiveness of lovers or husbands, who placed their mind and consciences in chador in order to invest their men with aphrodisiac power and feel comfortable as females beside more powerful men. By all means let us talk about the ways in which men threaten, subdue, overmaster us, but let us also look at the ways women belittle themselves and invite belittlement.

Why is it that stories of fathers and sons melt us while mothers and daughters must struggle not to be banal? Because when men, stoical and given to hiding their emotions, suddenly break through, the moment is charged with an intensity of pent-up feeling nothing else can match. Women, nurturers by definition, are expected to exude feeling and compassion. If the story of a woman struggling to hold down a job and raise a kid on her own were at the center of Kramer vs. Kramer, there would be no story. The chronicle of a man’s discovery of the woman in himself is a tale of expanded horizons, leading, in films like Woman of the Year and Tootsie, to funny and heartwarming epiphanies. A woman’s access to her masculine side is, however, a nastier proposition, a cautionary tale of shrinking humanity and loss of femininity.

As the brain scientists and philosophers now tell us, memory is a far more subjective and fluid affair than we have previously thought. Traditional models of the brain—a storehouse, a copy machine—are being rejected, while we come more and more to understand the active role we play in constructing the images that pass for memories. We go back to a film seen in childhood and find we have it all wrong—the tunnel was shorter and not as dark as we remembered; the shower scene was less explicit than our shrieking and bloody recollection. Not only that, but there were opposing images in a single film, a single frame: women were constantly being objectified and oppressed. Women were constantly holding their own and calling the shots. In fact, of course, both are true—woman as victim, woman as victor—but one view or the other will predominate according to changing political contexts and complicated and elusive personal agenda. I’m quite prepared to confess that something in my own particular childhood, some toxic mix of yearning and guilt, plus the Victorian scruples of my Southern WASP background, may have predisposed me toward films in which love revolves around taboo and the unobtainable and renunciation sends noble shivers down the spine. The tug o’ war between the erotics of concealment and of revelation, between denial and fulfillment, operates at every cinematic level; even the history of cinema reproduces it in the ongoing tension over censorship. Films made under the Production Code (the thirties to sixties) reflect traditional values of virginity, chastity, and, tied to sex’s indissoluble link with marriage and reproduction, woman’s power to say “no,” while the films made in recent permissive decades, featuring nudity and copulation a-go-go, presumably celebrate women’s sexual autonomy, thanks to feminism, the pill, and the severing of sex from procreation, yet show a corresponding loss of leverage in the mating game.

The same power shift can be seen in the making of movies, with women no longer at the center of male power fantasies, or even holding decent chips at the bargaining table. With women scorned, both as actresses and as target audiences, moviemaking, Hollywood style, has become a high-stakes macho poker game played by producers, agents, directors, and superstars.

Virility is measured in terms of the length of zeroes stretching after a digit, as in a $70,000,000 budget or four million for a screenplay, figures dutifully publicized and quoted, like a mantra, on Entertainment Tonight and in awed tones in the culture pages of our newspapers. My students feel more alienated from these high-explosive blockbusters than from the most lachrymose weepers of the thirties and forties. They don’t approve of heroines’ sacrifices in the name of love, yet their sheepish responses to such films as Letter from an Unknown Woman and Stella Dallas suggest that suffering for the “wrong man” is not unknown to them, nor are the themes—women’s complicated and often self-destructive ambition to serve as muse, model, Galatea to charismatic men—completely outdated. Movies operate on so many different levels; it’s why no single theory or approach can ever encompass all of cinema.

Conditions under which we view them, the zeitgeist, whether they’ve been overpraised or underrated—all play an enormous part in our perceptions of a film. But when we come to discuss or review a movie, we talk and write about it as if it is a mutually agreed-upon stable thing. We have to do this, otherwise we would be lost in a chaos of qualifications and miscommunications. And so we go on talking and writing, projecting and receiving fantasies, hoping to occasionally discover a mutual truth. Exiting a century in which marriage, monogamy, and the church no longer anchor our existence and entering one in which we can choose the sex of our children, prolong or end our lives, possibly redefine marriage or abandon it, we hardly know where we are going as a species, much less as individual men and women. But that’s what makes our surrogates in the movies so endlessly fascinating. If roles for women have declined, or splintered into subdivisions of class, ethnicity, and age, talking about them is a means of keeping sexual issues both on the table and mediated through the prism of a popular art form that belongs to us all. Feminists continue to bemoan the lack of a theory of female sexuality, but why should there be one? Why must we answer the question What Do Women Want?—a question posed by a man demanding a single, obvious explanation along the lines of male sexuality, a man who had said, more profoundly, that desire is by its very nature incapable of being satisfied . . . and, just as pessimistically, that men and women are always a phase apart.

This doesn’t mean that opportunities for women haven’t grown exponentially or that protest is futile. Indeed we are in the midst of a curious paradox, a conjunction of grievance and entitlement, that closely resembles the emergence of race as a paramount issue in the arts. Chris Rock joked that heretofore blacks were too worried about being lynched to concern themselves with whether or not they won Academy Awards. Women were too busy earning the right to work outside the home, and to have opinions at all, to agitate for executive positions.

Now there is a critical mass with voices and visibility, journalists and bloggers and critics who can amass the data, take to the media, and expose the shortcomings of Hollywood where women are concerned. Compared to the astonishing presence of women in the arts, on the internet, in public life—Out There and brimming with confidence in ways unimaginable thirty or even twenty years ago—the movie industry feels rearguard, the last bastion of boys-club supremacy, with the major companies engaged in an arms race after the blockbuster that is macho by definition. Why would any woman want to direct the next big-budget superhero action sequel or children’s fantasy for the global market? The excitement is elsewhere: in the expanding and metamorphosing roles for women in movies and, especially, on television. For instance, the recent spotlight on transgender issues can’t help but illuminate the slippery boundaries between male and female identities, wishes, desires, ways of being in the world, an almost frighteningly fluid continuum rather than a dichotomy. There are feminist online reviewers calling attention to gender stereotypes and demanding that movies adhere to some version of the Alison Bechdel test: every film should have (1) at least two women in it (2) who talk to each other, (3) about something besides a man. A pretty minimal request, but it’s a smart maxim that stays in the mind.

My own special delight—and possibly the surest sign of progress—is seeing women granted (almost) the same latitude as men, playing unpleasant and unromantic roles and getting away with it. Greta Gerwig, Lena Dunham, Tina Fey, Amy Poehler and Amy Schumer, Mary-Louise Parker, Claire Danes, Edie Falco, Julianne Moore, the Jennifers Lawrence and Aniston, Charlize Theron, the list goes on. At the moment, television, and the cable series, provide a showplace for the thoughtful, the edgy, the sexy, the rude, the bibulous, the mordant, the unexpected. Think of Frances McDormand as the New England termagant Olive Kitteridge. Or Robin Wright as a modern-day Lady Macbeth. Or the sinister Margo Martindale lying in wait in one series or another. Or Kerry Washington in Scandal, one of the many smart shows created by Shonda Rhimes, the show runner who has put so many black women on the TV map. Or the multi-ethnic-and gender cast of Orange Is the New Black. Or Elisabeth Moss as the outer-borough mouse who becomes a Madison Avenue ad exec. Or Edie Falco’s Jackie, dangerously addicted but so splendid as a nurse, so loving as a mother. These various stories, with their extraordinary scripts and ensembles, afford the luxury of watching a character full of contradictions, evolving (or not) over time.

Before its cable-driven renaissance, television was considered a “woman’s medium,” a (tame) refuge for all of us not included in that more remunerative demographic: Hollywood’s target male teenage audience. Now it’s more than a niche sanctuary; it’s the addictive go-to medium for grown-ups of both (or every) gender, and the gold standard for fresh and challenging women’s roles. If the last quarter century has taught us anything, it’s that cultural norms are mutable. Yet there’s also a certain melancholy tinge to our polemical assaults and clarion calls for change, a sense that some deep pull within us resists that change. The subtext of most critiques, including my own earlier one, is that Society (or the System) is at fault and something Must Be Done. I no longer see clear lines of guilt and responsibility but more often paradox: something lost, something gained, unconscious yearnings thwarting conscious aims.